Waite-Potter House

The house built by Thomas Waite in 1677 was a one room, one and one-half story building,

with a large stone fireplace incorporated into its interior side.

Known as a ‘’Rhode Island Stone Ender,’’ there are only a few remaining in Rhode Island today.

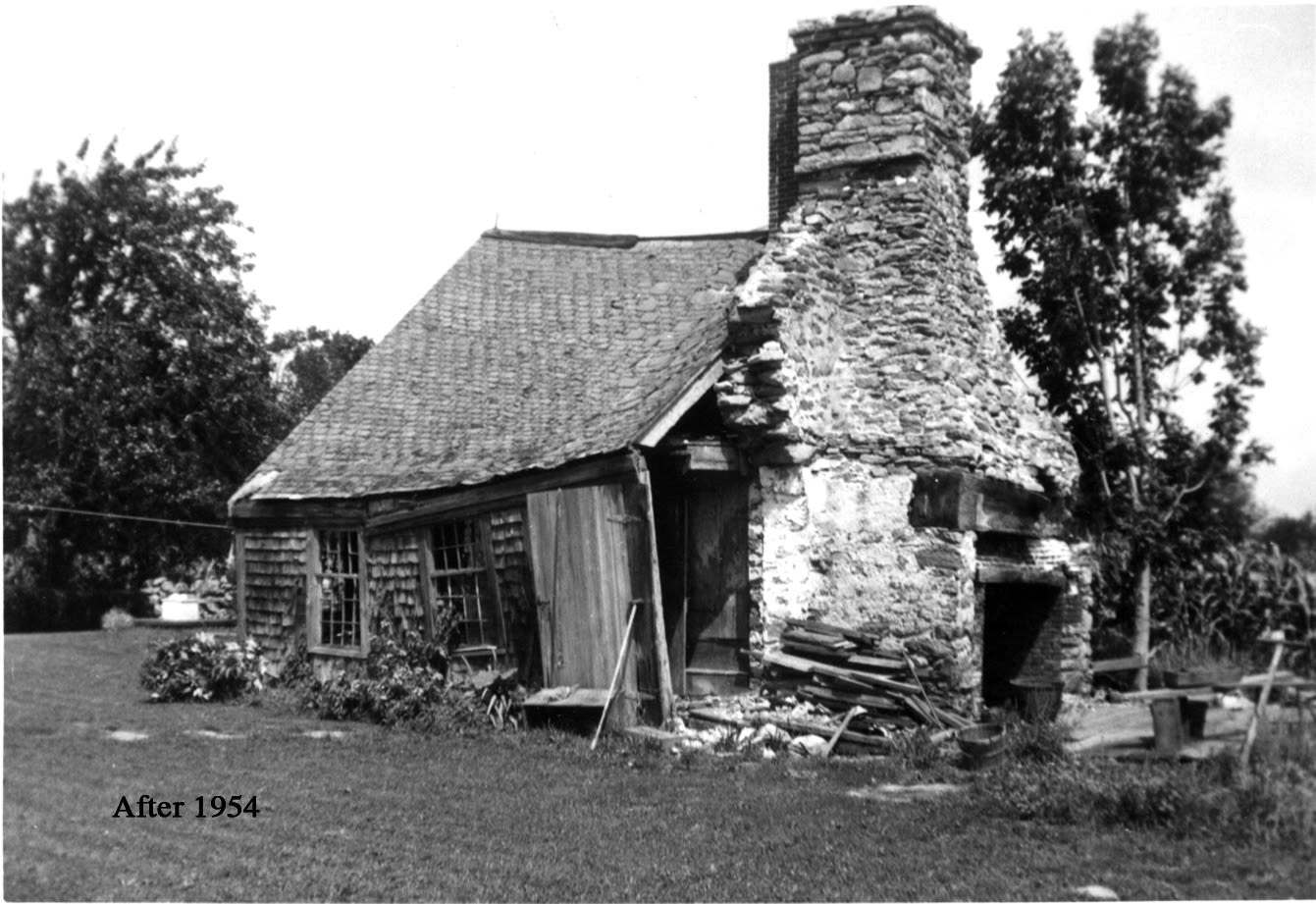

In 1728, Thomas Waite’s son Benjamin sold a portion of parcel to Robert Kirby, who in 1760 added one room to the opposite side of the stone chimney. After the Kirbys stopped living in the house, it was used as a farm building and pig pen. By 1945, the building was in disrepair, and in 1954, Hurricane Carol ripped the roof off the structure, leaving it open to rot and ruin. By 1962, the chimney had started to topple as the main support, the large oak lintel that held up the throat of the chimney, had rotted away and by 2006, everything had collapsed in the front. Although the house no longer stands, its image is on Westport's town seal.

As the site of significant archeological investigations, the property yields important information about early eighteenth-century life. Read more here.

Waite-Potter House Owners

From Anne W. Baker's presentation on Waite Potter House Restoration given in 2008 to the Westport Historical Society.

View Baker's full presentation slides with photographs and notes at https://docs.rwu.edu/baker_documentation/7/

The original farm on which this house was located included 200 acres on both sides of Main Road and as far east as the Noquochoke River. This large parcel was first owned by William Earle who had purchased it as part of the original division of land in Dartmouth. In 1661 Earle conveyed this 200 acres to Thomas Waite of Portsmouth, Rhode Island. By the time Thomas was 27 he had married Sarah Cook, moved to Dartmouth (Westport) and built this unique one room, one and one half story, ‘’Rhode Island Stone Ender.’’

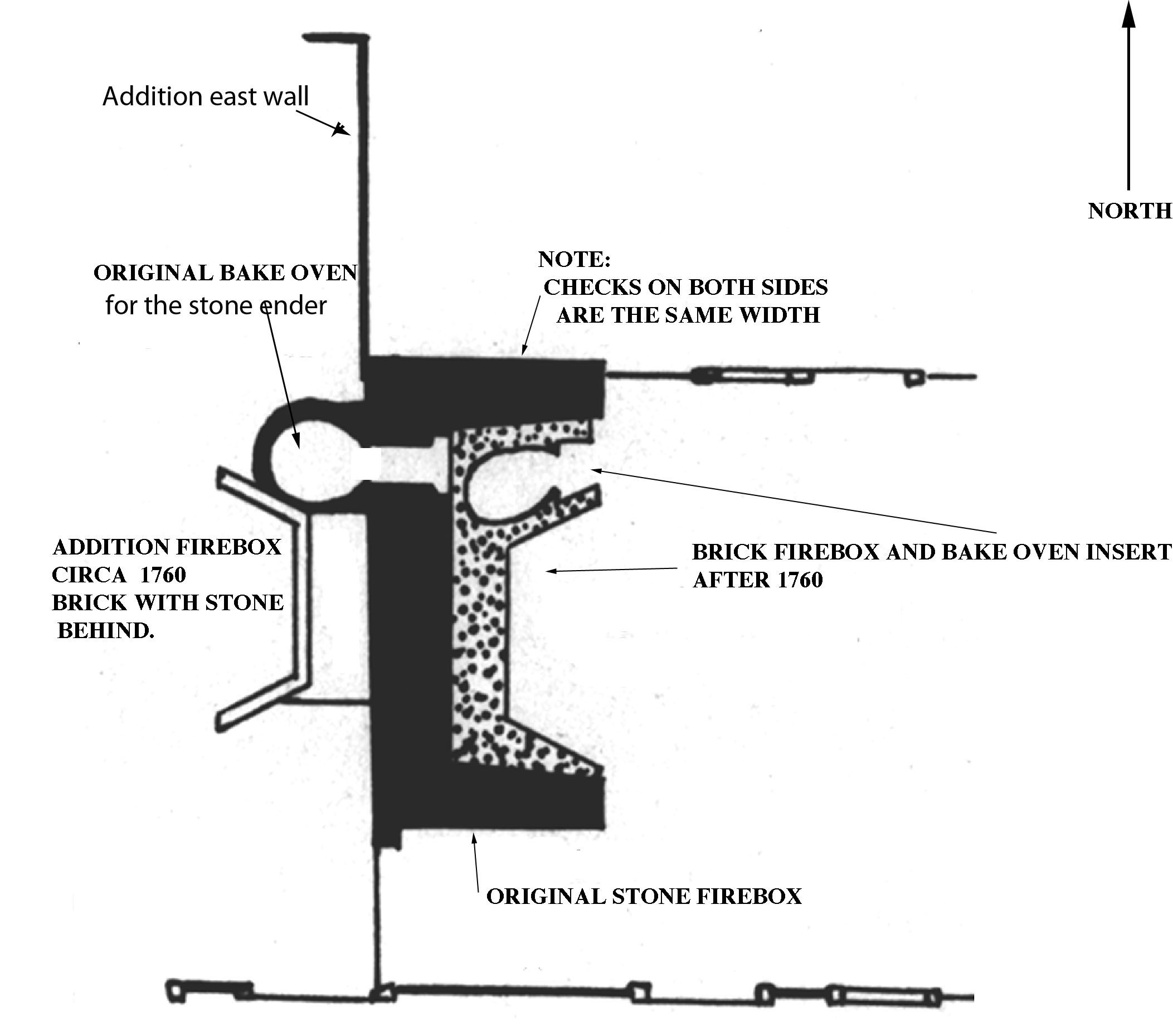

The farm remained in the Waite family for 60 years until 1728 when Benjamin, Thomas's son, sold the land between the river and Main Rd to Robert Kirby. Robert owned the property for 109 years. During that time, about 1760, he added a one room addition and brick chimney to the stone end of the original house. By 1836 the Kirby's had built a new house, a Cape, 25 feet west of the stone-ender. The original homestead, now empty, was used as a pig-sty, hen house and general farm purposes. Ichabod Kirby, Robert's son, sold the farm to Restcome Potter in 1837. In the deed to Mr. Potter a small piece of land was reserved for the Kirby burial lot. One of the rough stones in the lot has the initials R.K, and another I.K.

To this day the farm is still owned by the descendants of Restcome Potter. But I have often wonder why the house has never been referred to as the Waite/Kirby/Potter House. Certainly Kirby and Waite were most instrumental in the creation of Westport's earliest house.

By 1945 the house was in disrepair. Fortunately it had been well documented.

From Anne Baker's Personal Narrative on the Waite-Potter-Kirby House. Silent No Longer: A Personal Narrative

I can’t remember how I heard about a Rhode Island Stone-end House located in Westport with a legendary building date of 1677 although some historians argued that it was more likely built ten years earlier and others claimed later.

The house was in the woods, a half mile or so north of Central Village, Westport, Massachusetts (originally part of Dartmouth). Its rutted and narrow lane was shrouded by trees, their leaves just beginning to show a tinge of orange. Thick underbrush obscured my view on either side and I felt I was everywhere and nowhere all at once and I wondered if years ago Isham had traveled this same lane, but when I came to a clearing I saw a mid 18th century farm house, a Cape in design— old, but not a stone-ender. I shrugged my shoulders, straightened up and erased Isham from my mind.

As I turned to leave, a man with a neighborly smile and a black labrador dog by his side, approached my car. Dressed in a canvas jacket, blue overalls tucked into leather boots and a black baseball hat on his head, he looked to be the type of man one might find bird- watching. He told me his name was Edmie Bibeau and that he lived in the Cape with his wife Muriel. I apologized for trespassing and explained that I was looking for the remains of the oldest house in Westport. “You’ve got the right place.” he said, than pointed to a growth of ivy as huge as a elephant and explained that the house’s stone-end chimney and cellar hole were buried inside. Mr Bibeau went on to say that in the 1940s there had been an effort by local volunteers to save the house frame from collapsing. Due to lack of funds the idea never panned out and the house frame was blown down by hurricane Carol in 1954. Giving me permission to take a look, I first walked to the west side of the ivy, but all I could see was the crumbling ruins of a brick fireplace that appeared to be built hard up against a wall of stones. The shape of the firebox and size of the bricks suggested it was built in the late 1700s—perhaps an addition. The north view was hopelessly disguised by a dark impenetrable forest of tangled ivy, but the ivy on the east side was less invasive. As if my pupils were adjusting from dark to light I could see the outlines of the massive chimney of a Rhode Island Stone-ender. Despite a pile of fallen stones, poison ivy, and thorny thick bushes growing out of what might be a bottomless cellar 3hole, I was close enough to see that the chimney was hurting in spite of the cedar poles and bricks propping up its front in an heroic effort to prevent further collapse. Opened to the elements since the ‘54 hurricane, the original oak lintel (the beam that supports the chimney stones above the firebox opening) had rotted and was no longer able to hold the stones from falling out.

I began to worry how long the chimney could survive in this condition. Should I offer my help, except what could that be— or was it better to simply let the chimney surrender to time. I thought about restoration— paving over natural occurrences, but I also felt some things have to follow their natural course of deterioration and whatever I might do could misrepresent the original structure. On the other hand, I struggled with the knowledge of how rare this chimney was—an ancient expression of its own construction. Certainly in all of Bristol County, Massachusetts, there were no others. Was it an artifact, a memorial, or a great opportunity for learning about early New England architecture? I had to laugh at my self. What was I thinking? Of course I couldn’t do one or the other. I didn’t even own the place. I took some photos, and asked if I could return. I was assured “anytime.”

Read all of Baker's Personal Narrative on Waite Kirby Potter House including an excerpt from a report written by Norman Isham in 1903 about the Wait House

Waite Potter House in the 1930s.

Waite Potter House in the 1930s.

Waite Potter House after the 1954 Hurricane

Waite Potter House after the 1954 Hurricane

Drawing of the Bake Oven

Drawing of the Bake Oven

Restoring the chimney

Restoring the chimney

Restored Waite Potter Chimney

Restored Waite Potter Chimney

Photographs of the Chimney Restoration of Waite-Potter House completed in 2007. To see more photographs for Waite-Potter House go to https://docs.rwu.edu/baker_waite_potter_house/

Beginning of the Waite Potter Chimney restoration/conservation

Beginning of the Waite Potter Chimney restoration/conservation

Chimney after tree cut down, before the restoration, early 2007

Chimney after tree cut down, before the restoration, early 2007

Firebox Stone walls pointed during restoration

Firebox Stone walls pointed during restoration

View of the west end after stones pointed during restoration

View of the west end after stones pointed during restoration

Lintel Installation

Lintel Installation

New Lintel Installed

New Lintel Installed

Pointing the south end of the chimney

Pointing the south end of the chimney

Beehive Oven

Beehive Oven

Firebox Restoration

Firebox Restoration

Restored Chimney and Firebox

Restored Chimney and Firebox

Close-up View of Restoration

Close-up View of Restoration

View of the completed chimney restoration. October 2007.

View of the completed chimney restoration. October 2007.