Celebrating Franz Kafka

1883-1924

The 26th Annual John Howard Birss, Jr.

Memorial Program

2026

Celebrating Franz Kafka

1883-1924

The 26th Annual John Howard Birss, Jr.

Memorial Program

2026

Description of a Struggle:

1883-1906

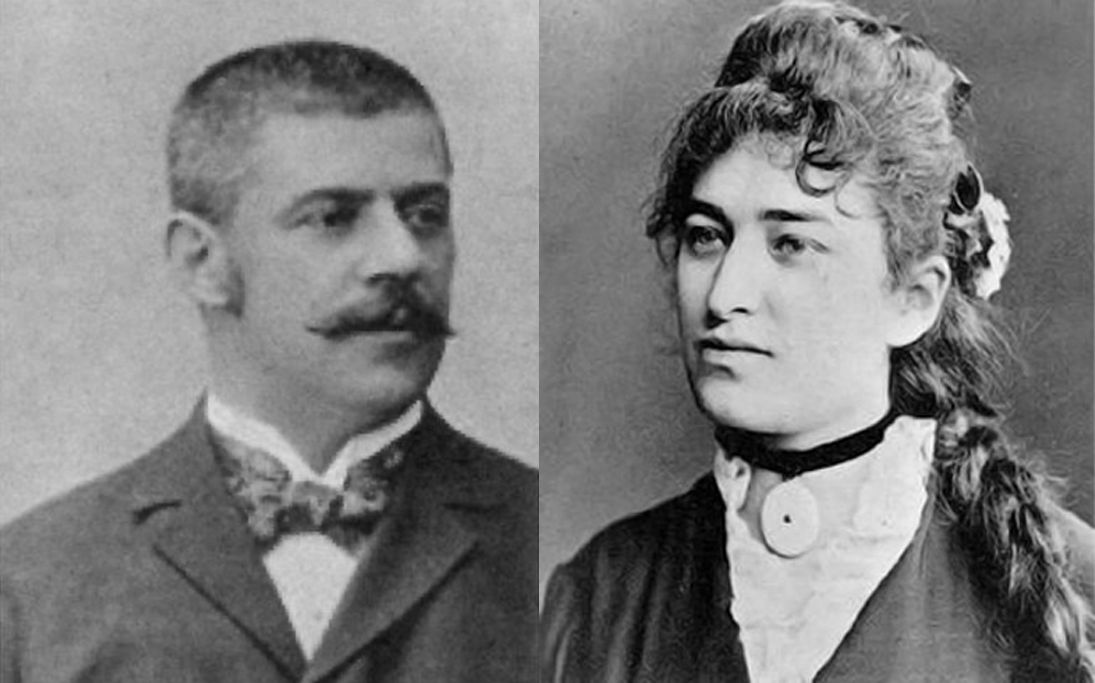

Franz Kafka was born July 3, 1883 to Hermann and Julie Kafka in Prague, near St. Nicholas Church Old Town. Two brothers — Georg (b. 1885) and Heinrich (b. 1887) — died in early childhood. Kafka also had three sisters — Elli (1889-1941), Valli (1890-1942), and Ottla (1892-1943) — who were murdered during the Holocaust. He lived with his parents until 1915.

While Kafka and his sisters, especially Ottla, were close, the same could not be said of his relationship with his father. Tension between the two influenced his decisions regarding his education, career, and relationships, as evidenced in Kafka's diaries and letters:

From Kafka's diaries, October 31, 1911:

"Lest I forget it, in case my father should call me a bad son once again, I’m writing down that in the presence of several relatives, for no special reason whether simply to oppress me or supposedly to save me he called Max “meshuggener ritoch” [Yiddish for crazy hothead] and that yesterday when Löwy was in my room he ironically shook his body and twisted his mouth while speaking of strange people being let into the apartment, what could interest one in a strange person, why one formed such useless relationships, etc. — I shouldn't have written it down after all, for I've positively written myself into hatred of my father, for which he has actually given no cause today and which at least with regard to Löwy is disproportionately great in comparison to my father's words as I have written them down and which even increases because I can't remember what was truly malicious in my father's behavior yesterday"

Source: Kafka, Franz. The Diaries. Translated by Ross Benjamin, First edition, Schocken Books, 2023, p. 109.

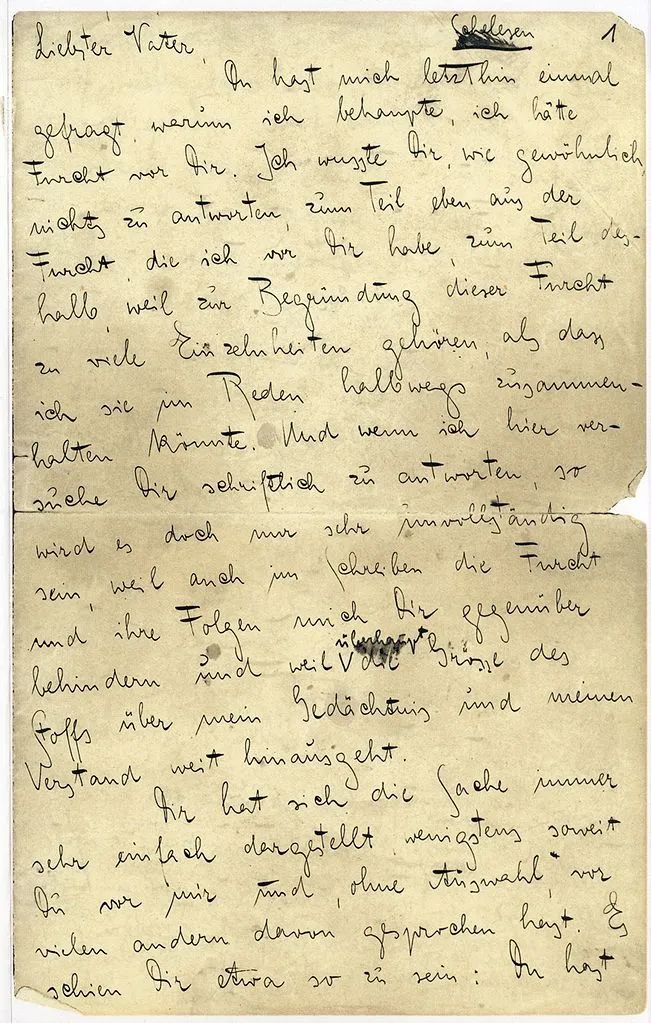

An 100 page handwritten letter to his father written in 1919 began,

"You asked me once recently why it is I maintain I am afraid of you. As usual, I wasn’t able to give you any answer, partly on account of that very fear, partly because if I am to explain the reasons for it, there are far too many relevant details for me to be able to hold them even halfway together when I speak about them. And if I try to answer you here on paper, it will still be very incomplete, because even in the writing, the fear and its consequences still get in the way when I am confronted with you, and because the sheer extent of the material goes far beyond my memory and my understanding."

Later Kafka wrote,

"You were closer to the mark with your dislike of my writing and of what, unbeknown to you, was connected with it. Here I had in fact escaped from you some little way by my own efforts, even if it did rather remind me of the worm whose tail had been trampled by a foot, but tears itself free and drags itself aside with its front. I was relatively safe; I was able to breathe again; for once, the dislike which of course you promptly felt for my writing too was actually welcome."

Source: Franz Kafka. The Metamorphosis and Other Stories. Translated by Joyce Crick. OUP Oxford, 2009, pp. 100-140.

Kafka gave the letter to his mother to give to his father. This she never did, instead returning it to her son. "Letter to the Father" was eventually published in 1952, after the deaths of Kafka and his father.

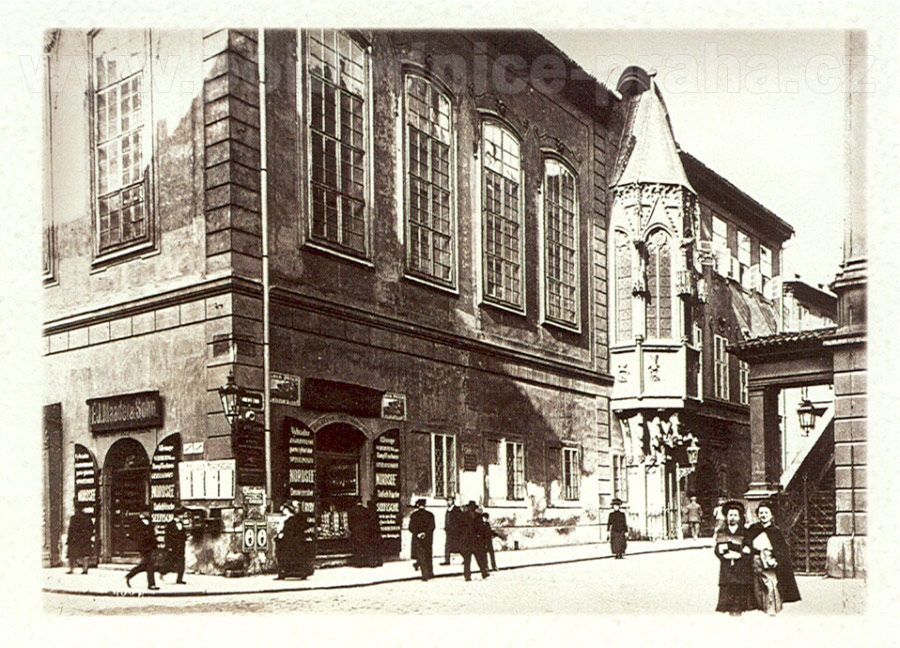

In 1901 Kafka enrolled in the German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, initially planning to study chemistry, but eventually deciding upon law. In his second year, on October 23, he met Max Brod who was reading a paper on Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. The two became lifelong friends and supporters of each other's writing. Kafka made Brod his literary executor.

Kafka's sisters: Elli, Valli and Ottla

Kafka's sisters: Elli, Valli and Ottla

Kafka's parents: Herman and Julien

Kafka's parents: Herman and Julien

From Kafka's "Letter to the Father" (Franz Kafka 1883-1924, Brief an den Vater, [1919], סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 029 Max Brod Archive)

From Kafka's "Letter to the Father" (Franz Kafka 1883-1924, Brief an den Vater, [1919], סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 029 Max Brod Archive)

German Charles-Ferdinand University

German Charles-Ferdinand University

Description of a Struggle: 1883-1906

Franz Kafka was born July 3, 1883 to Hermann and Julie Kafka in Prague, near St. Nicholas Church Old Town. Two brothers — Georg (b. 1885) and Heinrich (b. 1887) — died in early childhood. Kafka also had three sisters — Elli (1889-1941), Valli (1890-1942), and Ottla (1892-1943) — who were murdered during the Holocaust. He lived with his parents until 1915.

Kafka's sisters: Elli, Valli and Ottla

Kafka's sisters: Elli, Valli and Ottla

While Kafka and his sisters, especially Ottla, were close, the same could not be said of his relationship with his father. Tension between the two influenced his decisions regarding his education, career, and relationships, as evidenced in Kafka's diaries and letters:

From Kafka's "Letter to the Father" (Franz Kafka 1883-1924, Brief an den Vater, [1919], סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 029 Max Brod Archive)

From Kafka's "Letter to the Father" (Franz Kafka 1883-1924, Brief an den Vater, [1919], סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 029 Max Brod Archive)

From Kafka's diaries, October 31, 1911:

"Lest I forget it, in case my father should call me a bad son once again, I’m writing down that in the presence of several relatives, for no special reason whether simply to oppress me or supposedly to save me he called Max “meshuggener ritoch” [Yiddish for crazy hothead] and that yesterday when Löwy was in my room he ironically shook his body and twisted his mouth while speaking of strange people being let into the apartment, what could interest one in a strange person, why one formed such useless relationships, etc. — I shouldn't have written it down after all, for I've positively written myself into hatred of my father, for which he has actually given no cause today and which at least with regard to Löwy is disproportionately great in comparison to my father's words as I have written them down and which even increases because I can't remember what was truly malicious in my father's behavior yesterday"

Source: Kafka, Franz. The Diaries. Translated by Ross Benjamin, First edition, Schocken Books, 2023, p. 109.

The 100 page handwritten letter to his father written in 1919 began,

"You asked me once recently why it is I maintain I am afraid of you. As usual, I wasn’t able to give you any answer, partly on account of that very fear, partly because if I am to explain the reasons for it, there are far too many relevant details for me to be able to hold them even halfway together when I speak about them. And if I try to answer you here on paper, it will still be very incomplete, because even in the writing, the fear and its consequences still get in the way when I am confronted with you, and because the sheer extent of the material goes far beyond my memory and my understanding."

Later Kafka wrote,

"You were closer to the mark with your dislike of my writing and of what, unbeknown to you, was connected with it. Here I had in fact escaped from you some little way by my own efforts, even if it did rather remind me of the worm whose tail had been trampled by a foot, but tears itself free and drags itself aside with its front. I was relatively safe; I was able to breathe again; for once, the dislike which of course you promptly felt for my writing too was actually welcome."

Source: Franz Kafka. The Metamorphosis and Other Stories. Translated by Joyce Crick. OUP Oxford, 2009, pp. 100-140.

Kafka's parents: Herman and Julien

Kafka's parents: Herman and Julien

Kafka gave the letter to his mother to give to his father. This she never did, instead returning it to her son. "Letter to the Father" was eventually published in 1952, after the deaths of Kafka and his father.

In 1901 Kakfa enrolled in the German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, initially planning to study chemistry, but eventually deciding upon law. In his second year, on October 23, he met Max Brod who was reading a paper on Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. The two became lifelong friends and supporters of each other's writing. Kafka made Brod his literary executor.

German Charles-Ferdinand University

German Charles-Ferdinand University

Resolutions:

1906-1912

Kafka received his law degree in July 1906. As was required for lawyers who wanted to enter civil service, he worked in Prague's civil and criminal courts for one year. During this probationary year he took a course in industrial insurance at the German Commercial Academy in Prague.

After his clerkship, Kafka was hired by the Italian insurance company Assicurazioni Generali in November 1907. He was expected to work 10 hours a day and he resigned only eight months later looking for better options.

In a letter to Hedwig Weiler, whom Kafka met at his Uncle Siegfried Löwy's during the summer of 1907, he wrote:

"My life is completely chaotic now. At any rate I have a job with a tiny salary of 80 crowns and an infinite eight to nine hours of work; but I devour the hours outside the office like a wild beast. Since I was not previously accustomed to limiting my private life to six hours, and since I am also studying Italian and want to spend the evenings of these lovely days out of doors, I emerge from the crowdedness of my leisure hours feeling scarcely rested."

Source: Kafka, Franz. Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors. Schocken Books, 1977.

Kafka found what he wanted at the Workers Accident Insurance Institute in Prague a few weeks later. He worked conscientiously, Monday to Saturday, from 8.00 a.m. till 2.00 p.m. The job was not a demanding one and Kafka frequently described it to his friends as “dull,” but the 6 hour work day, allowing him more time to write and travel, was to his liking.

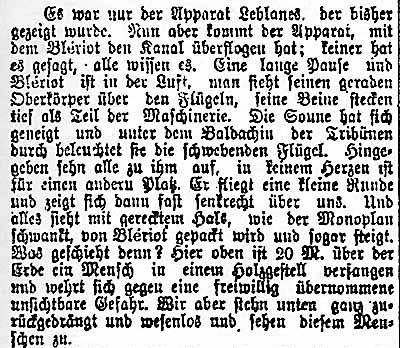

In 1909 Kafka's account of an air competition "Die Aeroplane in Brescia," which he attended with Brod and Brod's brother Otto while vacationing in Italy, appeared in the Prague newspaper Bohemia (September 29). The following excerpt from Kafka's newspaper story (transcribed opposite) tells of Louis Bleriot's appearance at the airshow.

Excerpt from Kafka's "Die Aeroplane in Brescia"

Excerpt from Kafka's "Die Aeroplane in Brescia"

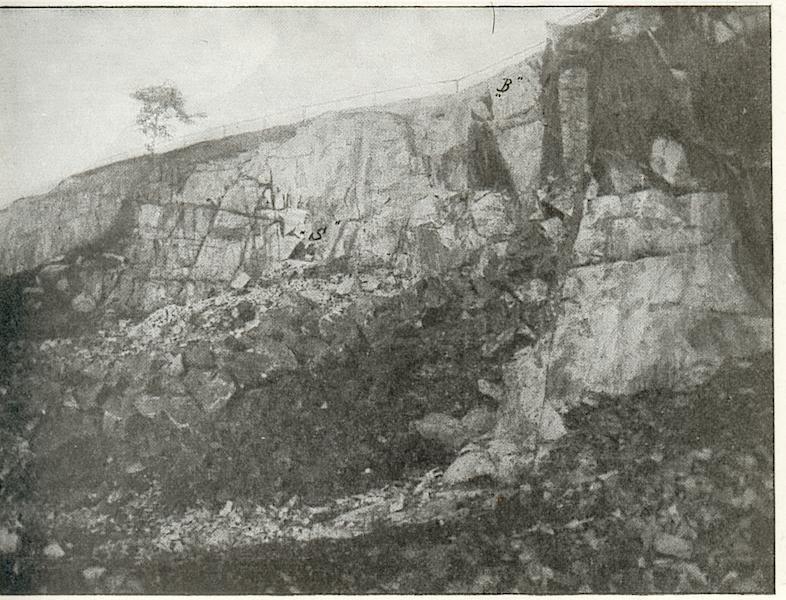

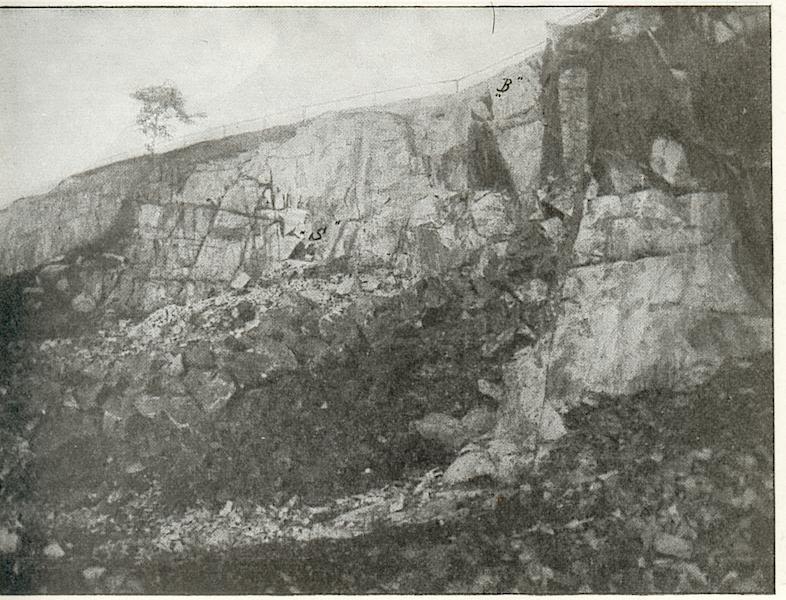

His duties as an insurance clerk included risk classification (which involved evaluating the degree of danger of a certain job, and so setting the level of premium to be paid by business owners), improving the Institute’s efforts at accident prevention, and the writing of articles and talks for the Institute. Among the numerous reports he prepared was one on accident prevention in quarries, which included photographs illustrating dangers such as rolling debris and rubble. This report was written in 1914, the same year Kafka began writing The Trial, the final scene of which takes place in a quarry.

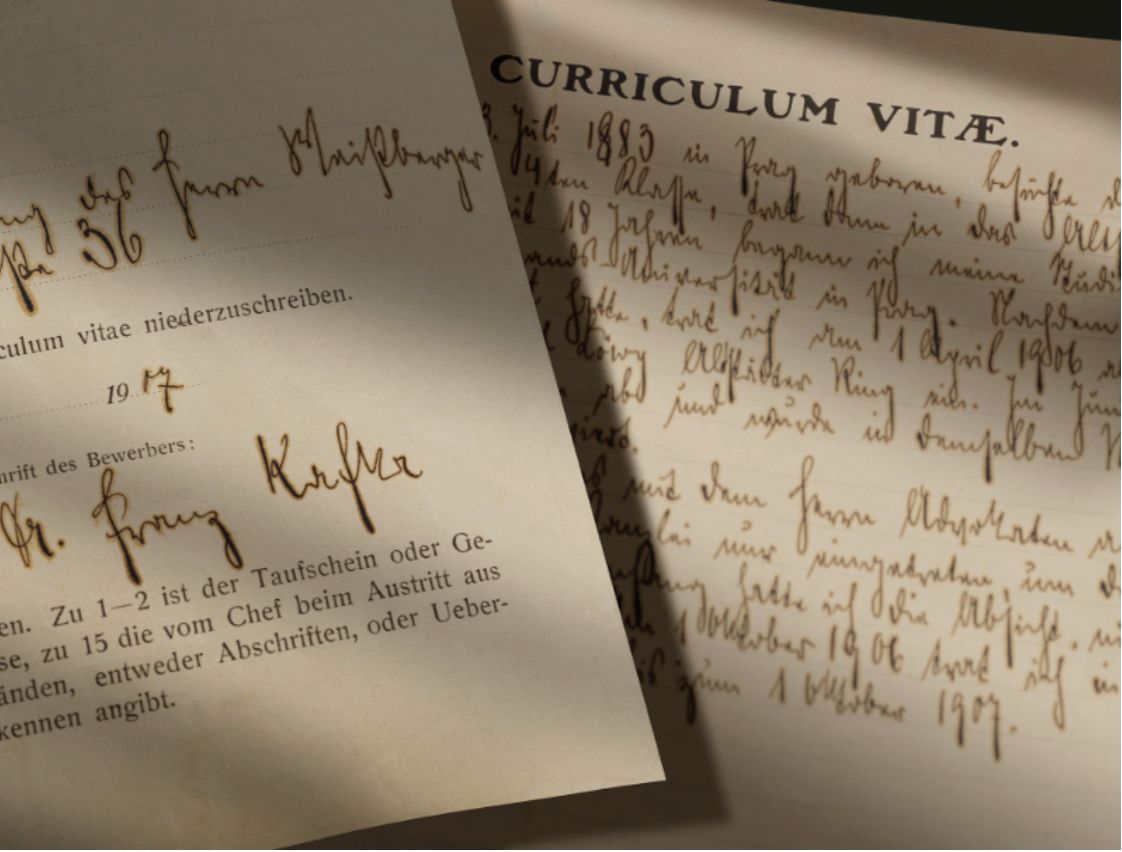

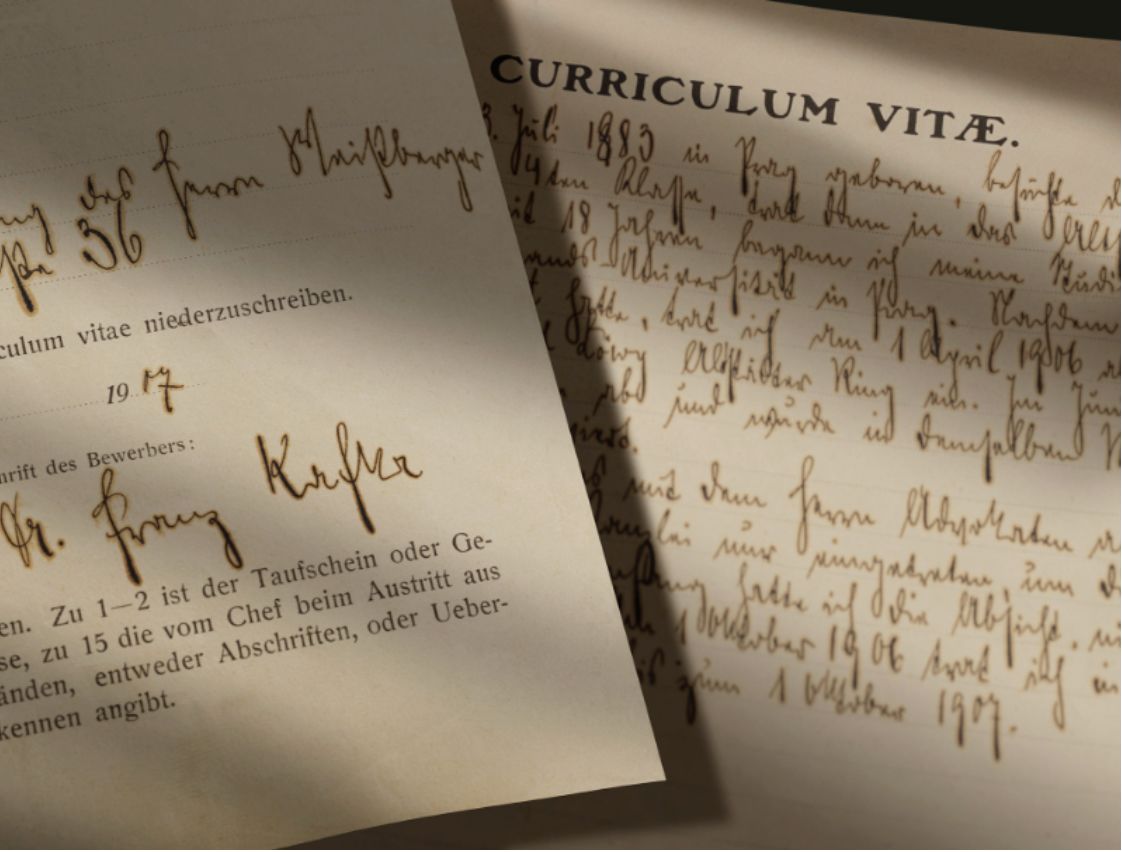

Kafka's job application and curriculum vitae (1907)

Kafka's job application and curriculum vitae (1907)

Workers Accident Insurance Institute in Prague

Workers Accident Insurance Institute in Prague

From "The Aeroplanes of Brescia":

It was only Leblanc's aircraft that had been shown so far. But now comes the machine which Blériot flew across the Channel; no one has it, everyone knows. A long pause and Blériot is in the air, we can see his upper body erect over the wings, his legs extend far down, becoming part of the machinery. The sun has dipped lower, and its rays shine through beneath the canopy over the grandstand, illuminating the hovering wings. Everyone looks up at him enthralled ; no heart has room for anyone else. He flies a little circle and then appears above us, almost vertically. And, craning their necks, everyone looks on as the monoplane wobbles, but Blériot seizes control and it even climbs. What is happening? Up there, 20 m[eters] above the earth, a man is trapped in a wooden frame, defending himself against an invisible danger that he has chosen freely. But we stand down below, pressed back and insubstantial, looking at this man.

Source: Stach, Reiner. Is That Kafka?: 99 Finds. Translated by Kurt Beals, New Directions Books, 2016, p. 216.

Photograph, showing "a loose stone block" from Kafka's 1914 report on accident prevention in quarries

Photograph, showing "a loose stone block" from Kafka's 1914 report on accident prevention in quarries

Resolutions: 1906-1912

Kafka received his law degree in July 1906. As was required for lawyers who wanted to enter civil service, he worked in Prague's civil and criminal courts for one year. During this probationary year he took a course in industrial insurance at the German Commercial Academy in Prague.

Kafka's job application and curriculum vitae (1907)

Kafka's job application and curriculum vitae (1907)

After his clerkship, Kafka was hired by the Italian insurance company Assicurazioni Generali in November 1907. He was expected to work 10 hours a day and he resigned only eight months later looking for better options.

In a letter to Hedwig Weiler, whom Kafka met at his Uncle Siegfried Löwy's during the summer of 1907, he wrote:

"My life is completely chaotic now. At any rate I have a job with a tiny salary of 80 crowns and an infinite eight to nine hours of work; but I devour the hours outside the office like a wild beast. Since I was not previously accustomed to limiting my private life to six hours, and since I am also studying Italian and want to spend the evenings of these lovely days out of doors, I emerge from the crowdedness of my leisure hours feeling scarcely rested."

Source: Kafka, Franz. Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors. Schocken Books, 1977.

Kafka found what he wanted at the Workers Accident Insurance Institute in Prague a few weeks later. He worked conscientiously, Monday to Saturday, from 8.00 a.m. till 2.00 p.m.

Workers Accident Insurance Institute

Workers Accident Insurance Institute

The job was not a demanding one and Kafka frequently described it to his friends as “dull,” but the 6 hour work day, allowing him more time to write and travel, was to his liking.

In 1909 Kafka's account of an air competition "Die Aeroplane in Brescia," which he attended with Brod and Brod's brother Otto while vacationing in Italy, appeared in the Prague newspaper Bohemia (September 29). The following excerpt from Kafka's newspaper story tells of Louis Bleriot's appearance at the airshow.

Excerpt from Kafka's "Die Aeroplane in Brescia"

Excerpt from Kafka's "Die Aeroplane in Brescia"

From "The Aeroplanes of Brescia":

It was only Leblanc's aircraft that had been shown so far. But now comes the machine which Blériot flew across the Channel; no one has it, everyone knows. A long pause and Blériot is in the air, we can see his upper body erect over the wings, his legs extend far down, becoming part of the machinery. The sun has dipped lower, and its rays shine through beneath the canopy over the grandstand, illuminating the hovering wings. Everyone looks up at him enthralled ; no heart has room for anyone else. He flies a little circle and then appears above us, almost vertically. And, craning their necks, everyone looks on as the monoplane wobbles, but Blériot seizes control and it even climbs. What is happening? Up there, 20 m[eters] above the earth, a man is trapped in a wooden frame, defending himself against an invisible danger that he has chosen freely. But we stand down below, pressed back and insubstantial, looking at this man.

Source: Stach, Reiner. Is That Kafka?: 99 Finds. Translated by Kurt Beals, New Directions Books, 2016, p. 216.

His duties as an insurance clerk included risk classification (which involved evaluating the degree of danger of a certain job, and so setting the level of premium to be paid by business owners), improving the Institute’s efforts at accident prevention, and the writing of articles and talks for the Institute. Among the numerous reports he prepared was one on accident prevention in quarries, which included photographs illustrating dangers such as rolling debris and rubble. This report was written in 1914, the same year Kafka began writing The Trial, the final scene of which takes place in a quarry.

Photograph, showing "a loose stone block" from Kafka's 1914 report on accident prevention in quarries

Photograph, showing "a loose stone block" from Kafka's 1914 report on accident prevention in quarries

The Departure:

1912-1924

Kafka met Felice Bauer, a cousin of Max Brod visiting from Berlin, in the summer of 1912. He first wrote to her on September 20, beginning a relationship that would last until 1917. Although they rarely saw each other in person, their correspondence amounted to close to 500 letters and they were twice engaged. Shortly after their meeting, Kafka wrote the short story "The Judgement" in a single sitting on the night September 22-23, 1912. Kafka dedicated the story to Felice.

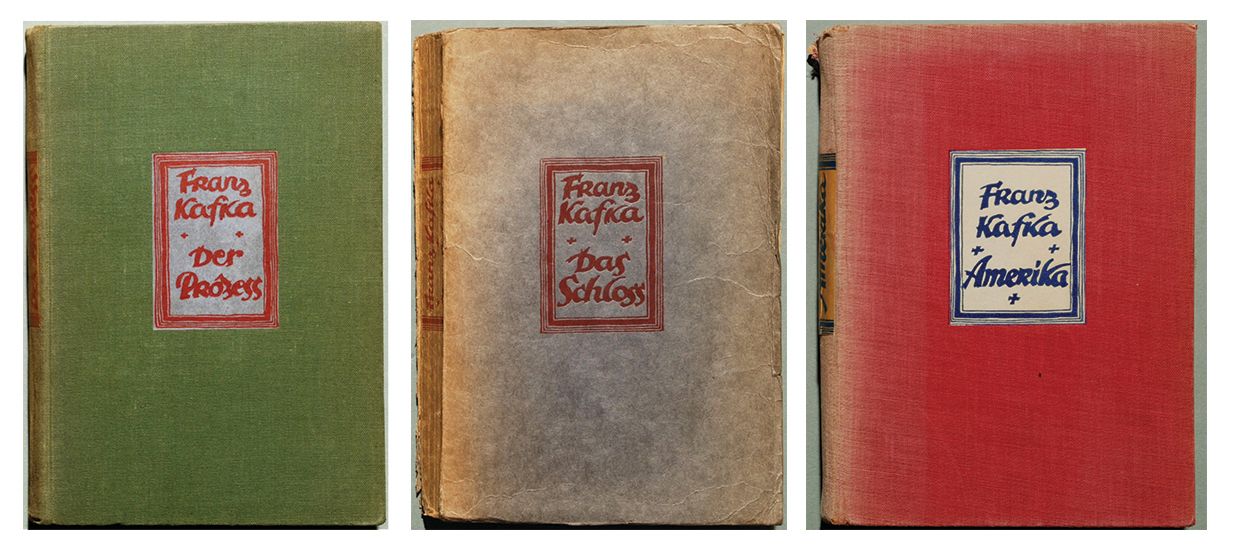

Earlier in the year, Brod had introduced Kafka to Kurt Wolff who would play an important role in his life. In November 1912 Wolff's publishing house published Contemplation, a collection of 18 stories, which he dedicated to Max. Wolff continued to promote and publish Kafka's works, including "The Metamorphosis" (1916).

In 1913 Kafka published the short story "The Stoker," which became the first chapter of his unfinished novel The Man Who Disappeared. After Kafka's death Brod would complete the unfinished novel and publish it as Amerika.

Kafka met Milena Jesenská when she wrote him to ask permission to translate "The Stoker" into Czech. This led to a passionate relationship, consisting of almost daily letters, written primarily between April and November 1920. They met only a few times, once for four days in Vienna. While their relationship ended early in 1921, Kafka gave Milena his diaries later that year and they continued to correspond until his death. She would also become the first translator of several of Kafka's short stories into Czech, including "The Judgment," "Metamorphosis," and "Contemplation."

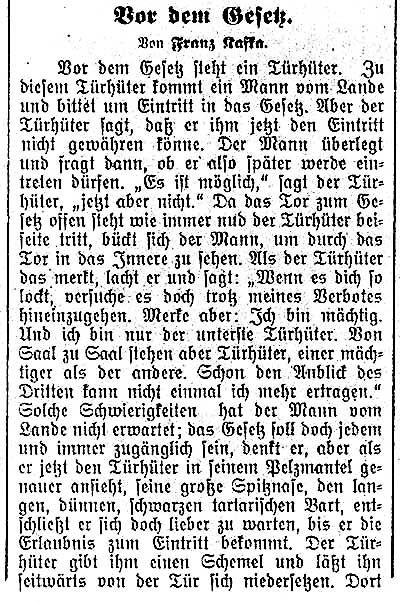

Kafka wrote the parable "Before the Law" in the winter of 1914 and first published it as a standalone piece in Prague's Zionist weekly newspaper Selbstwehr (1915) and two more times — as part of the Expressionist literary almanac The Last Judgment (1916) and in his collection A Country Doctor (1919). Kafka would later use the parable in The Trial (as part of the chapter "In the Cathedral").

From Kafka's diaries:

"Instead of working — I have written only one page (exegesis of the legend) — read parts of finished chapters and found some of them good. Always in the awareness that every feeling of satisfaction and happiness, such as I have especially with respect to the legend, must be paid for and indeed in order to preclude any recovery must be paid for afterward."

Source: Kafka, Franz. The Diaries. Translated by Ross Benjamin, First edition, Schocken Books, 2023, p.317.

Though Kafka's parents were Jewish and he learned some Hebrew as a boy, it wasn't until 1917, after being diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis that Kafka began to study Hebrew seriously. Kafka's interest in Zionism continued to grow and he seemed to consider settling in Palestine.

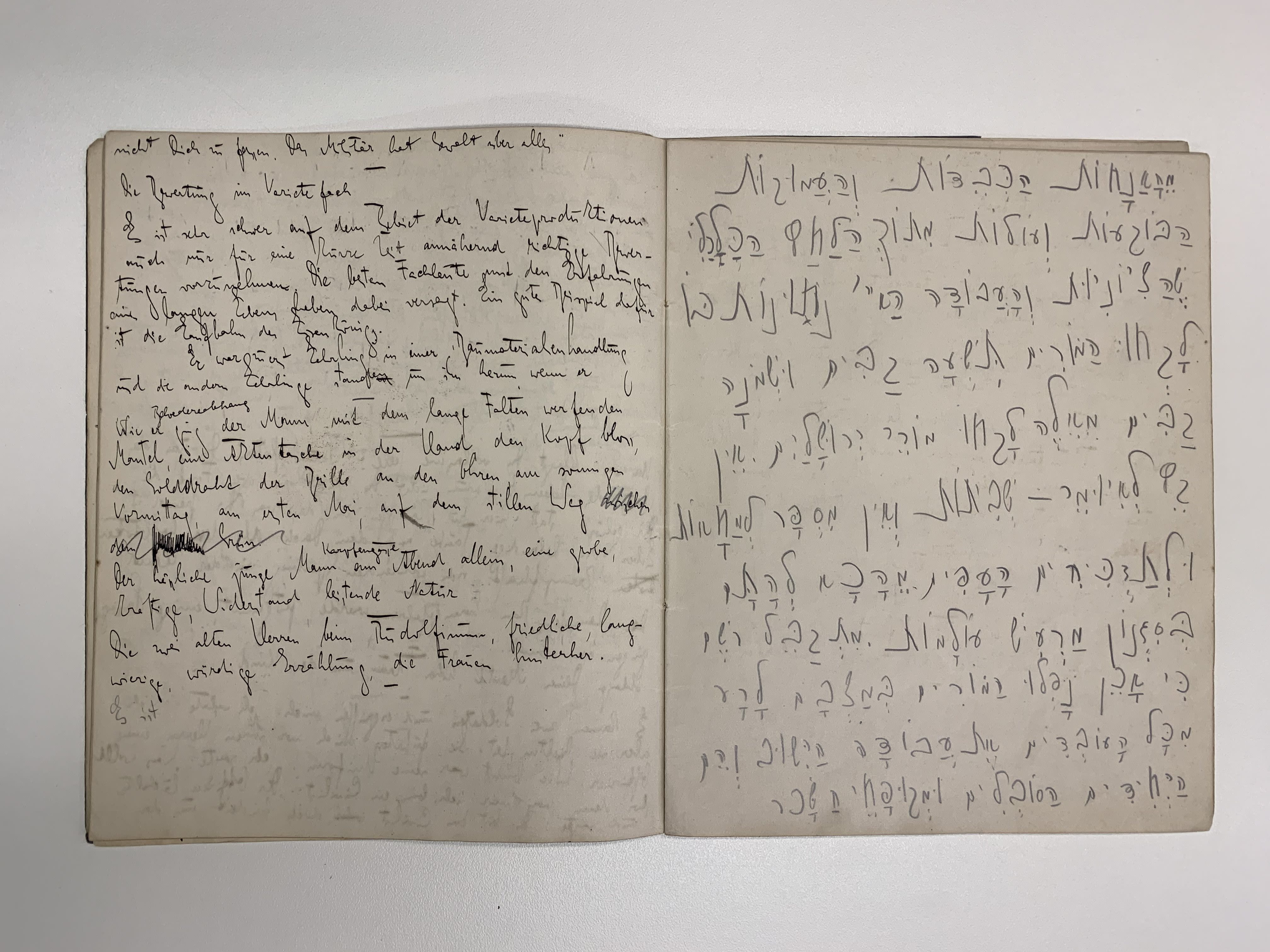

Page with Hebrew-German vocabulary in Kafka's own hand, from his Blue Notebook (Kafka, Franz, 1917-1924, ARC. 4* 2000 05 034 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel)

Page with Hebrew-German vocabulary in Kafka's own hand, from his Blue Notebook (Kafka, Franz, 1917-1924, ARC. 4* 2000 05 034 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel)

Plagued with illness and numerous stays in sanatoriums over the years, Kafka was granted early retirement from the Workers Accident Insurance Institute in 1922. In the same year, he began working on The Castle.

Kafka met Dora Diamant in July 1923. Having fallen in love, he moved to Berlin for a short period to be near her. When illness forced him to move to Vienna for treatment at a hospital there, Dora went with him. He spent the final six weeks of his life at Kierling Sanatorium, near Vienna, with Dora at his side. As talking, swallowing and breathing became increasingly difficult, near the end of his life Kafka could only consume calorie-rich liquids, like beer, and communicate with "conversation slips." He died on June 3, 1924 and was was buried eight days later at the New Jewish Cemetery in Prague.

Kafka published two collections of stories, Contemplation and A Country Doctor, during his lifetime. He was preparing A Hunger Artist, a collection of stories, for publication in his final days. "Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk" was the last piece he wrote. Kafka left far more unpublished and unfinished pieces than he published. Before his death he asked Brod to destroy all his work.

After Kafka's death, and in spite of his request to destroy all his writings, Brod published The Trial (Verlag Die Schmiede, 1925) and the two other unfinished novels - The Castle (Kurt Wolff Verlag, 1926) and Amerika (Kurt Wolff Verlag, 1927). Over the next 12 years Brod published every novel, novella, and short story that Kafka wrote, including "Description of a Struggle," which he originally began in 1904 and gave to Brod in 1910 writing that "what pleases me most about the novella, dear Max, is that it's out of the house" (March 18, 10).

Cover of first German editions of The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika

Cover of first German editions of The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika

From first letter to Felice Bauer, Sept. 20, 1912:

"In the likelihood that you no longer have even the remotest recollection of me, I am introducing myself once more: my name is Franz Kafka, and I am the person who first greeted you for the first time that evening at Director Brod's in Prague, the one who subsequently handed you across the table, one by one, photographs of a Thalia trip, and who finally, with the very hand now striking the keys, held your hand, the one which you confirmed a promise to accompany him next year to Palestine."

Source: Kafka, Franz, and Felice Bauer. Letters to Felice. Edited by Erich Heller and Jürgen Born, Translated by James Stern and Elisabeth Duckworth, [First English edition], Schocken Books, 1973.

“Before the Law.” Selbstwehr, Sept. 1915

"Before the law stands a doorkeeper. A man from the country comes to this doorkeeper, and asks for admission to the law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant him admission now. The man reflects, and then asks if he will therefore be permitted to enter later. “It is possible,” the doorkeeper says, “but not now.”"

"Before the law stands a doorkeeper. A man from the country comes to this doorkeeper, and asks for admission to the law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant him admission now. The man reflects, and then asks if he will therefore be permitted to enter later. “It is possible,” the doorkeeper says, “but not now.”"

Source: Mark Harman (in Kafka, Franz. Selected Stories. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2024, p.186.)

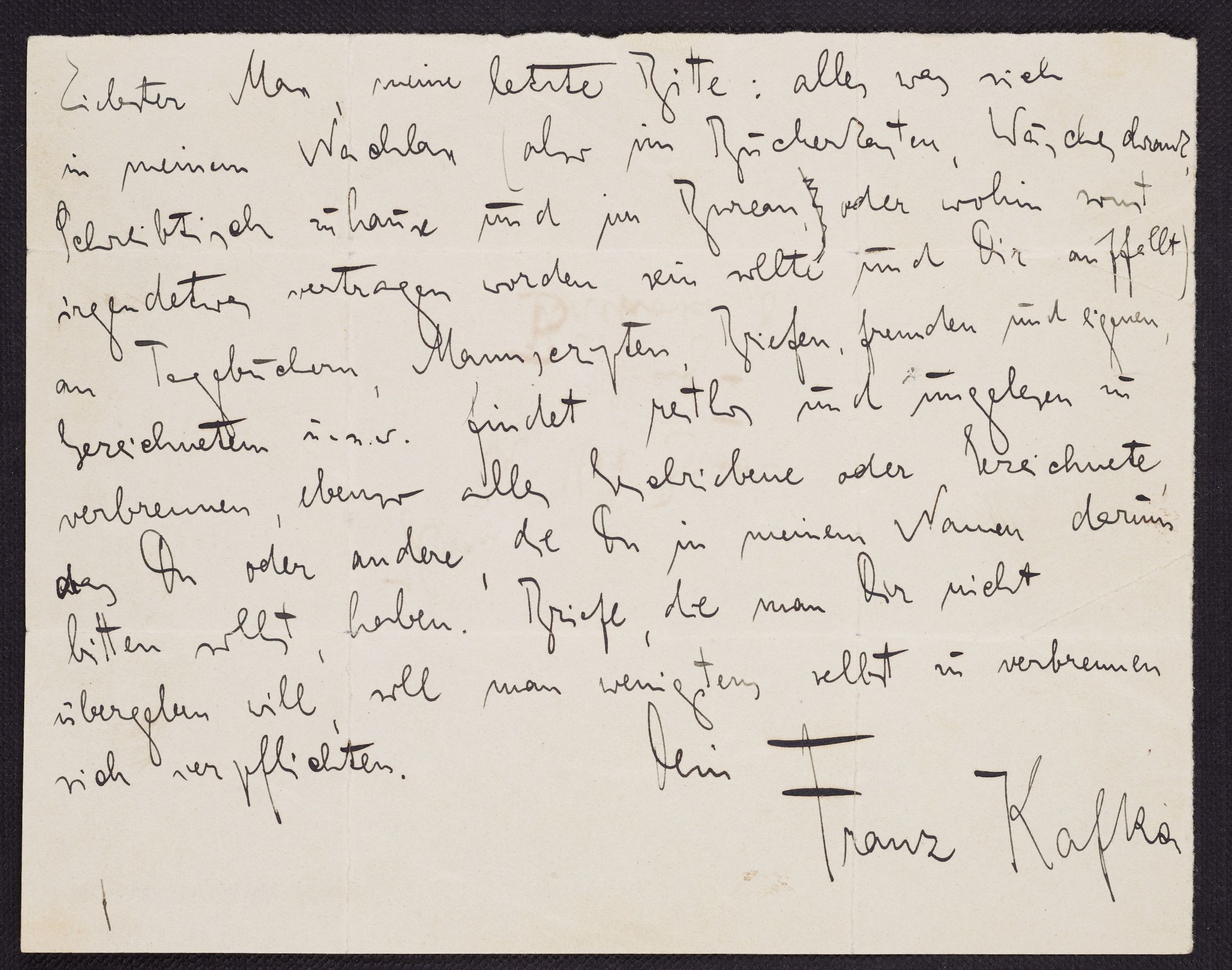

Kafka's Testamente, 1921 (ARC. 4* 2000 05 050 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel): Dearest Max, my final request: whatever diaries, manuscripts, letters from myself or others, drawings etc. you find among the things I leave behind (i.e. in my book cabinet, linen cupboard, desk at home or at the office, or wherever else you might come across them), please burn every bit of it without reading it, and do the same with any writings or drawings you have, o that you can obtain from others, whom you should ask on my behalf. Those who do not wish to return the letters to you should at least commit to burning them themselves.

Kafka's Testamente, 1921 (ARC. 4* 2000 05 050 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel): Dearest Max, my final request: whatever diaries, manuscripts, letters from myself or others, drawings etc. you find among the things I leave behind (i.e. in my book cabinet, linen cupboard, desk at home or at the office, or wherever else you might come across them), please burn every bit of it without reading it, and do the same with any writings or drawings you have, o that you can obtain from others, whom you should ask on my behalf. Those who do not wish to return the letters to you should at least commit to burning them themselves.

Source: Stach, Reiner. Is That Kafka?: 99 Finds. Translated by Kurt Beals, New Directions Books, 2016, p. 270.

Letter to Max, November 1922:

"Dear Max, this time I really might not get up again; the chances of lung inflammation are good enough after a month of lung fever, and not even the fact that I’m writing it down can keep it at bay, although this does have a certain power.

In the case that this should happen, this is my last will and testament regarding everything I have written:

My only writings that count are the books: Judgment, Stoker, Metamorphosis, Penal Colony, Country Doctor, and the story: Hunger Artist. (The few copies of Contemplation may be kept; I don't want to put anyone to the trouble of pulping them, but nothing from it may be reprinted.) When I say that those five books and the story count, I don't mean that I wish for them to be reprinted and passed down to posterity, to the contrary, if they were to be completely forgotten, that would be in keeping with my actual wishes. But since they’re already there, I won’t prevent anyone from preserving them, should he so choose.

On the other hand, everything else I have written (whether printed in magazines, in manuscript, or letters) should without exception, insofar as it is obtainable or can be retrieved from the addressees upon (after all you know most of the addressees, primarily they are Mrs. Felice M., Mrs. Julie nee Wohryzek, and Mrs. Milena Pollak; please take particular care not to forget the few notebooks Mrs. Pollak has) — all of this should, without exception and preferably without being read (though I won't deny the opportunity to peek)—all of this should be burned without exception, and I ask you to do so as soon as possible."

Source: Stach, Reiner. Is That Kafka?: 99 Finds. Translated by Kurt Beals, New Directions Books, 2016, p. 271.

Excerpt from Milena Jesenská's obituary for Kafka, which appeared in the Czech newspaper Národní Listy:

"He was shy, anxious, meek, and kind, yet the books he wrote are gruesome and painful. He saw the world as full of invisible demons, tearing apart and destroying defenseless humans…He has written the most significant books of modern German literature, books that embody the struggle of today's generation throughout the world-while refraining from all tendentiousness..."

Source: Kafka, Franz. Letters to Milena. Translated by Philip Boehm, Schocken Books, 1990.

The Departure: 1912-1924

Kafka met Felice Bauer, a cousin of Max Brod visiting from Berlin, in the summer of 1912. He first wrote to her on September 20, beginning a relationship that would last until 1917. Although they rarely saw each other in person, their correspondence amounted to close to 500 letters and they were twice engaged. Shortly after their meeting, Kafka wrote the short story "The Judgement" in a single sitting on the night September 22-23, 1912. Kafka dedicated the story to Felice.

From first letter to Felice Bauer, Sept. 20, 1912:

"In the likelihood that you no longer have even the remotest recollection of me, I am introducing myself once more: my name is Franz Kafka, and I am the person who first greeted you for the first time that evening at Director Brod's in Prague, the one who subsequently handed you across the table, one by one, photographs of a Thalia trip, and who finally, with the very hand now striking the keys, held your hand, the one which you confirmed a promise to accompany him next year to Palestine."

Source: Kafka, Franz, and Felice Bauer. Letters to Felice. Edited by Erich Heller and Jürgen Born, Translated by James Stern and Elisabeth Duckworth, [First English edition], Schocken Books, 1973.

Earlier in the year, Brod had introduced Kafka to Kurt Wolff who would play an important role in his life. In November 1912 Wolff's publishing house published Contemplation, a collection of 18 stories, which he dedicated to Max. Wolff continued to promote and publish Kafka's works, including "The Metamorphosis" (1916).

In 1913 Kafka published the short story "The Stoker," which became the first chapter of his unfinished novel The Man Who Disappeared. After Kafka's death Brod would complete the unfinished novel and publish it as Amerika.

Kafka met Milena Jesenská when she wrote him to ask permission to translate "The Stoker" into Czech. This led to a passionate relationship, consisting of almost daily letters, written primarily between April and November 1920. They met only a few times, once for four days in ViennaThey met only a few times, once for four days in Vienna. While their relationship ended early in 1921, Kafka gave Milena his diaries later that year and they continued to correspond until his death. Milena would also become the first translator of several of Kafka's short stories into Czech, including "The Judgment," "Metamorphosis," and "Contemplation."

Kafka wrote the parable "Before the Law" in the winter of 1914 and first published it as a standalone piece in Prague's Zionist weekly newspaper Selbstwehr (1915) and two more times — as part of the Expressionist literary almanac The Last Judgment (1916) and in his collection A Country Doctor (1919). Kafka would later use the parable in The Trial (as part of the chapter "In the Cathedral").

"Before the law stands a doorkeeper. A man from the country comes to this doorkeeper, and asks for admission to the law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant him admission now. The man reflects, and then asks if he will therefore be permitted to enter later. “It is possible,” the doorkeeper says, “but not now.”"

"Before the law stands a doorkeeper. A man from the country comes to this doorkeeper, and asks for admission to the law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant him admission now. The man reflects, and then asks if he will therefore be permitted to enter later. “It is possible,” the doorkeeper says, “but not now.”"

Source: Mark Harman (in Kafka, Franz. Selected Stories. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2024, p.186.)

From Kafka's diaries:

"Instead of working — I have written only one page (exegesis of the legend) — read parts of finished chapters and found some of them good. Always in the awareness that every feeling of satisfaction and happiness, such as I have especially with respect to the legend, must be paid for and indeed in order to preclude any recovery must be paid for afterward."

Source: Kafka, Franz. The Diaries. Translated by Ross Benjamin, First edition, Schocken Books, 2023, p.317.

Though Kafka's parents were Jewish and he learned some Hebrew as a boy, it wasn't until 1917, after being diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis that Kafka began to study Hebrew seriously. Kafka's interest in Zionism continued to grow and he seemed to consider settling in Palestine.

Page with Hebrew-German vocabulary in Kafka's own hand, from his Blue Notebook (Kafka, Franz, 1917-1924, ARC. 4* 2000 05 034 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel)

Page with Hebrew-German vocabulary in Kafka's own hand, from his Blue Notebook (Kafka, Franz, 1917-1924, ARC. 4* 2000 05 034 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel)

Plagued with illness and numerous stays in sanatoriums over the years, Kafka was granted early retirement from the Workers Accident Insurance Institute in 1922. In the same year, he began working on The Castle.

Kafka met Dora Diamant in July 1923. Having fallen in love, he moved to Berlin for a short period to be near her. When illness forced him to move to Vienna for treatment at a hospital there, Dora went with him. He spent the final six weeks of his life at Kierling Sanatorium, near Vienna, with Dora at his side. As talking, swallowing and breathing became increasingly difficult, near the end of his life Kafka could only consume calorie-rich liquids, like beer, and communicate with "conversation slips." He died on June 3, 1924 and was was buried eight days later at the New Jewish Cemetery in Prague.

Kafka published two collections of stories, Contemplation and A Country Doctor, during his lifetime. He was preparing A Hunger Artist, a collection of stories, for publication in his final days. "Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk" was the last piece he wrote. Kafka left far more unpublished and unfinished pieces than he published. Before his death he asked Brod to destroy all his work.

Kafka's Testamente, 1921 (ARC. 4* 2000 05 050 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel): Dearest Max, my final request: whatever diaries, manuscripts, letters from myself or others, drawings etc. you find among the things I leave behind (i.e. in my book cabinet, linen cupboard, desk at home or at the office, or wherever else you might come across them), please burn every bit of it without reading it, and do the same with any writings or drawings you have, o that you can obtain from others, whom you should ask on my behalf. Those who do not wish to return the letters to you should at least commit to burning them themselves.

Kafka's Testamente, 1921 (ARC. 4* 2000 05 050 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel): Dearest Max, my final request: whatever diaries, manuscripts, letters from myself or others, drawings etc. you find among the things I leave behind (i.e. in my book cabinet, linen cupboard, desk at home or at the office, or wherever else you might come across them), please burn every bit of it without reading it, and do the same with any writings or drawings you have, o that you can obtain from others, whom you should ask on my behalf. Those who do not wish to return the letters to you should at least commit to burning them themselves.

Letter to Max, November 1922:

"Dear Max, this time I really might not get up again; the chances of lung inflammation are good enough after a month of lung fever, and not even the fact that I’m writing it down can keep it at bay, although this does have a certain power.

In the case that this should happen, this is my last will and testament regarding everything I have written:

My only writings that count are the books: Judgment, Stoker, Metamorphosis, Penal Colony, Country Doctor, and the story: Hunger Artist. (The few copies of Contemplation may be kept; I don't want to put anyone to the trouble of pulping them, but nothing from it may be reprinted.) When I say that those five books and the story count, I don't mean that I wish for them to be reprinted and passed down to posterity, to the contrary, if they were to be completely forgotten, that would be in keeping with my actual wishes. But since they’re already there, I won’t prevent anyone from preserving them, should he so choose.

On the other hand, everything else I have written (whether printed in magazines, in manuscript, or letters) should without exception, insofar as it is obtainable or can be retrieved from the addressees upon (after all you know most of the addressees, primarily they are Mrs. Felice M., Mrs. Julie nee Wohryzek, and Mrs. Milena Pollak; please take particular care not to forget the few notebooks Mrs. Pollak has) — all of this should, without exception and preferably without being read (though I won't deny the opportunity to peek)—all of this should be burned without exception, and I ask you to do so as soon as possible."

Source: Stach, Reiner. Is That Kafka?: 99 Finds. Translated by Kurt Beals, New Directions Books, 2016, p. 271.

After Kafka's death, and in spite of his request to destroy all his writings, Brod published The Trial (Verlag Die Schmiede, 1925) and the two other unfinished novels - The Castle (Kurt Wolff Verlag, 1926) and Amerika (Kurt Wolff Verlag, 1927). Over the next 12 years Brod published every novel, novella, and short story that Kafka wrote, including "Description of a Struggle," which he originally began in 1904 and gave to Brod in 1910 writing that "what pleases me most about the novella, dear Max, is that it's out of the house" (March 18, 10).

Cover of first German editions of The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika

Cover of first German editions of The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika

Excerpt from Milena Jesenská's obituary for Kafka, which appeared in the Czech newspaper Národní Listy:

"He was shy, anxious, meek, and kind, yet the books he wrote are gruesome and painful. He saw the world as full of invisible demons, tearing apart and destroying defenseless humans…He has written the most significant books of modern German literature, books that embody the struggle of today's generation throughout the world-while refraining from all tendentiousness..."

Source: Kafka, Franz. Letters to Milena. Translated by Philip Boehm, Schocken Books, 1990.

Old Town,

where Kafka was born July 3, 1883

Workers Accident Insurance Institute,

where Kafka worked 1908-1922

German Student Reading and Lecture Hall,

where Kafka first met Max Brod in 1903

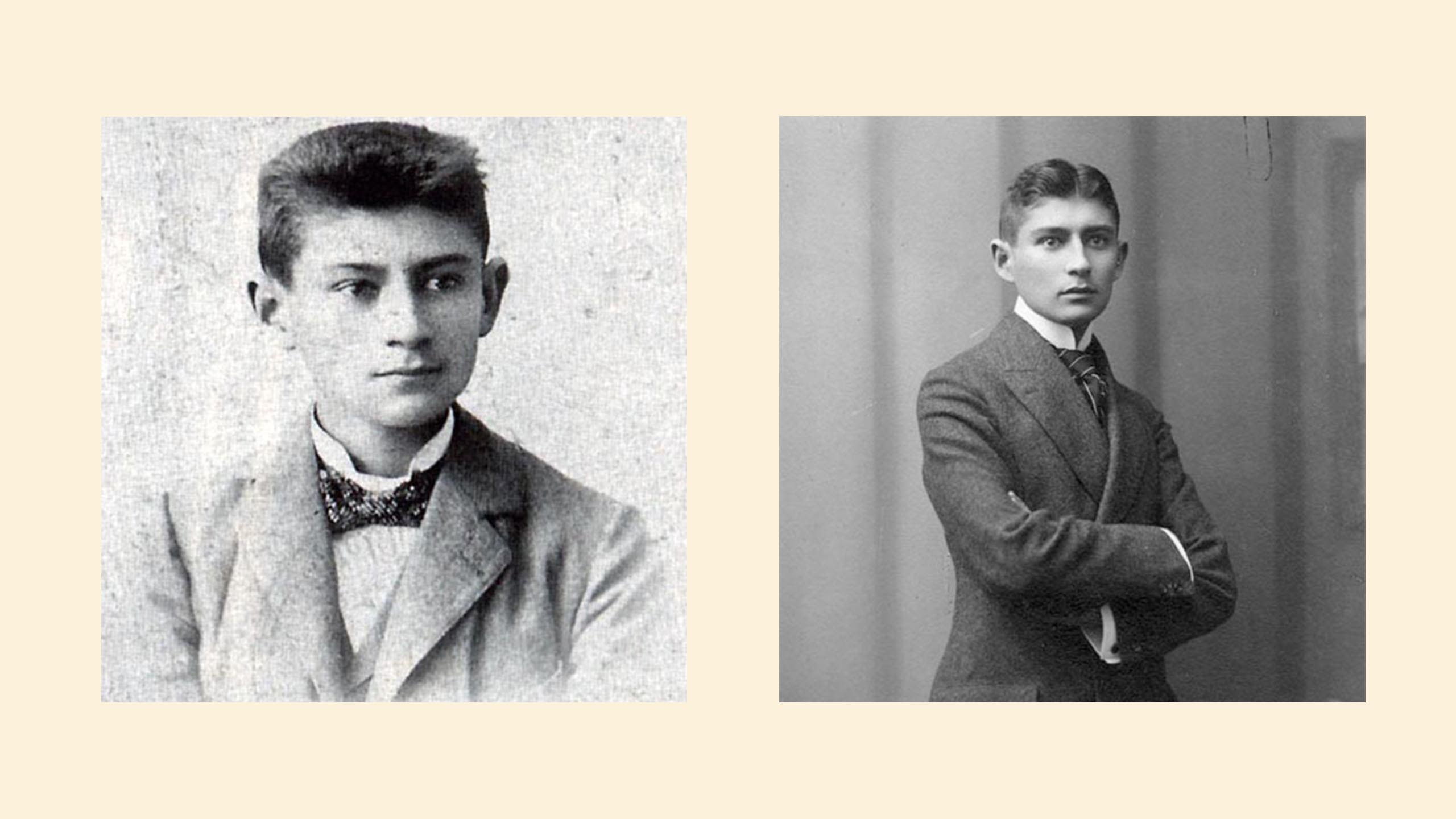

Max Brod, 1914

Max Brod, 1914

Civilian Swimming School,

could be seen from the apartment where Kafka and his parents lived on Mikulášská Street, 1907-1913. He wrote in his diary that he went to the Swimming School on the day Germany declared war on Russia.

(The Diaries, Translated by Ross Benjamin, p.285)

Kafka lived at his sister Valli's on Bilek Street in the summer of 1914 and and then at his sister Elli's on Nerudova Street from September 1914-February 1915. He began writing The Trial while staying in these temporary residences.

In his diary Kafka described Chotek Gardens, near Prague Castle, as "Most beautiful place in Prague. Birds sang, the castle with the gallery, the old trees bedecked with last year’s foliage, the semidarkness," and on May 5 (1915) he wrote, "Nothing, dull slightly aching head. In the afternoon Chotek Gardens, read Strindberg, who nourishes me."

(The Diaries, Translated by Ross Benjamin, pp. 386 and 392)

Schönborn Palace,

another temporary residence:

Kafka rented a small apartment there in 1917 (March-September).

New Jewish Cemetery,

in the Strašnice neighborhood,

where Kafka is buried

(not on the map)

An Old Manuscript: Restoring The Trial and Other Works

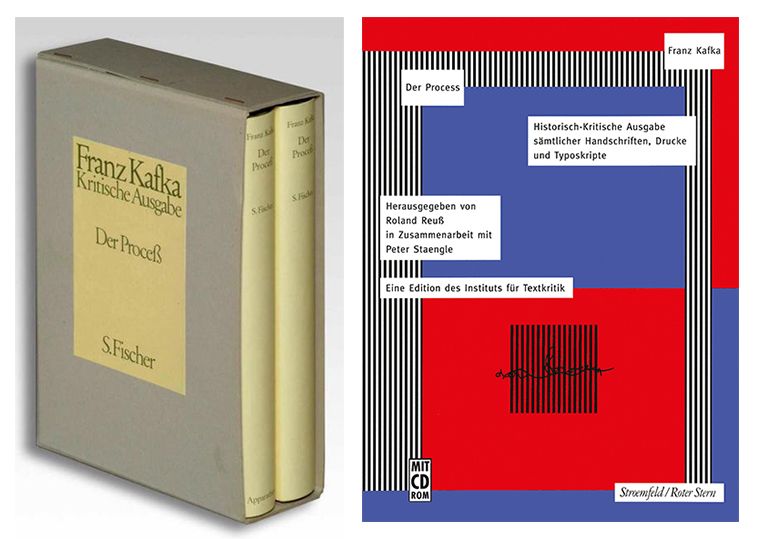

Shortly after World War I broke out, Kafka began working on The Trial in 1914, writing chapters and chapter sections in ten different notebooks. He read the first chapter aloud to Max in September 1914, who recalled that Kafka laughed so much "that there were moments when he couldn't read any further." Kafka read aloud other chapters in the following months, but abandoned the project in early 1915, leaving behind more than a dozen bundles of loose-leaf notes. He gave these to Max in 1920.

Before publishing the novel, Brod edited it, standardizing Kafka's spelling and punctuation, excising some bits, and completing other unfinished parts. Brod considered each bundle a “chapter” and arranged them in an order he thought worked. While the manuscript gave no title, according to Brod Kafka had referred to it as “The Trial” in his diaries and conversation. On April 26, 1925, Brod published The Trial, followed by the Castle and Amerika in 1926 and 1927.

Brod offered the Jewish publishing house Schocken Verlag rights to Kafka's work and in 1935 they published The Trial, along with The Castle and Amerika, giving Kafka widespread distribution in Germany. Edwin and Willa Muir translated the first English editions (Victor Gollancz) — The Castle in 1930, The Trial in 1937, and Amerika in1938.

Brod fled to Tel Aviv in 1939, taking with him Kafka's manuscript of The Trial and other unpublished papers. Brod released a new German edition of The Trial (Schocken Books, New York, 1946) with material he had previously omitted — incomplete chapters and passages struck by Kafka. The Muirs followed with an updated English edition (Modern Library, 1956) which included new material translated by E.M. Butler. More English translations of The Trial followed, along with translations into over 50 different languages, including Czech in 1958. (Click here for more details about the publication history of Kafka's novels.)

After Max Brod's death in 1968, new German versions began to appear. The Bodleian Library, Oxford University, had received the bulk of Kafka's original manuscripts from his heirs in 1961. Malcolm Pasley, German literary scholar and editor, then began restoring the original German texts to their unexpurgated and unfinished state, including Kafka's unique punctuation, considered critical to his style. In 1982 S. Fischer Verlag published The Castle as a two-volume set — the novel in the first volume, and the fragments, deletions, and editor's notes in the second volume.

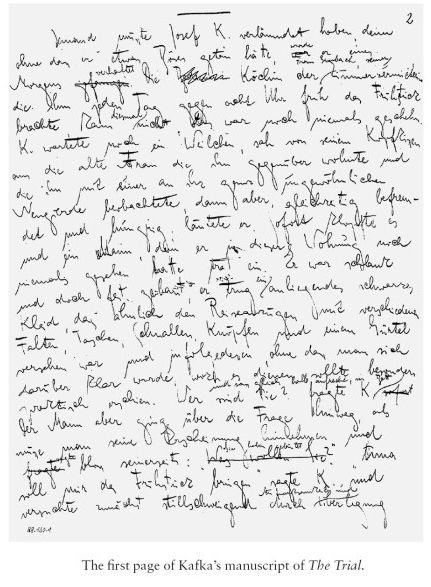

Similarly, after Kafka's original manuscript of The Trial was auctioned to the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, Germany in 1988, Pasley and his team set to work again. They published the new critical edition Der Prozess, also as a two-volume set, with S. Fischer Verlag in 1990. An historical-critical edition, Der Process, published by Stroemfeld/Roter Stern Verlag followed in 1995, complete with a facsimile of Kafka's own handwriting, rather than a printed transcription of it, displaying all Kafka's changes. This edition consists of sixteen individually bound booklets, each corresponding to a segment of the original manuscript. They are interchangeable and can be read in any conceivable order.

Pasley's work restoring Kafka's original manuscripts informed new English translations and in the 1990s, Schocken began publishing these, including Breon Mitchell's translation of The Trial (1998) and Mark Harman's translations of The Castle (1998) and Amerika: The Missing Person (2008).

Kafka left behind a diary (1910-1924), which Brod edited as he did the novels. A two volume English edition came out, the first volume translated by Joseph Kresh in 1948 and the second one by Martin Greenberg in 1949, with the cooperation of Hannah Arendt, who was then editorial director of Schocken Books.

S. Fischer Verlag published an uncensored German edition of the diaries in 1990. Using this restored edition and Kafka's original entries, which included self-reflections, records of daily events, and drafts of literary works, Ross Benjamin began working on a new English translation of Kafka's diaries in 2014, with the aim of catching Kafka in the act of writing and presenting the diaries not as a cohesive whole, as Brod’s version did. Schocken published Benjamin's translation of The Diaries in 2022, complete with spelling mistakes, scraps of abandoned stories, and entries that break off in mid-sentence and appear to be out of sequence.

Today the Bodleian and Marbach Libraries are not the only ones holding Kafka’s original works. When Brod died in 1968 he left his literary estate to his secretary Esther Hoffe. The Tel Aviv court ruled that Brod had explicitly ordered Hoffe to catalogue and transfer his papers to a public archive. In 2016, Israel's National Library was awarded the papers and manuscripts and began collecting them from sites in Israel, Germany, and a Swiss bank vault. They have since been digitizing the collection and making it available online.

On writing The Trial, from Kafka’s diary:

August 21, 1914

"Began with such hopes and was thrown back by all three stories, today most of all. Perhaps it’s correct that work could be done on the Russian story only always after The Trial. In this ridiculous hope, which is evidently based on a mechanical fantasy, I begin the Trial again.–It wasn’t completely in vain."

September 13, 1914

"Again barely 2 pages. At first I thought the sadness about the Austrian defeats and the fear of the future (a fear that seems to me basically ridiculous and at the same time disgraceful) would hinder me altogether from writing. It wasn’t that only a dullness, which perpetually returns and must be perpetually overcome. For the sadness itself there’s time enough when not writing..."

Source: Kafka, Franz. The Diaries, Translated by Ross Benjamin, First edition, Schocken Books, 2023, pp. 355-356.

New German editions of The Trial (1990 and 1995)

New German editions of The Trial (1990 and 1995)

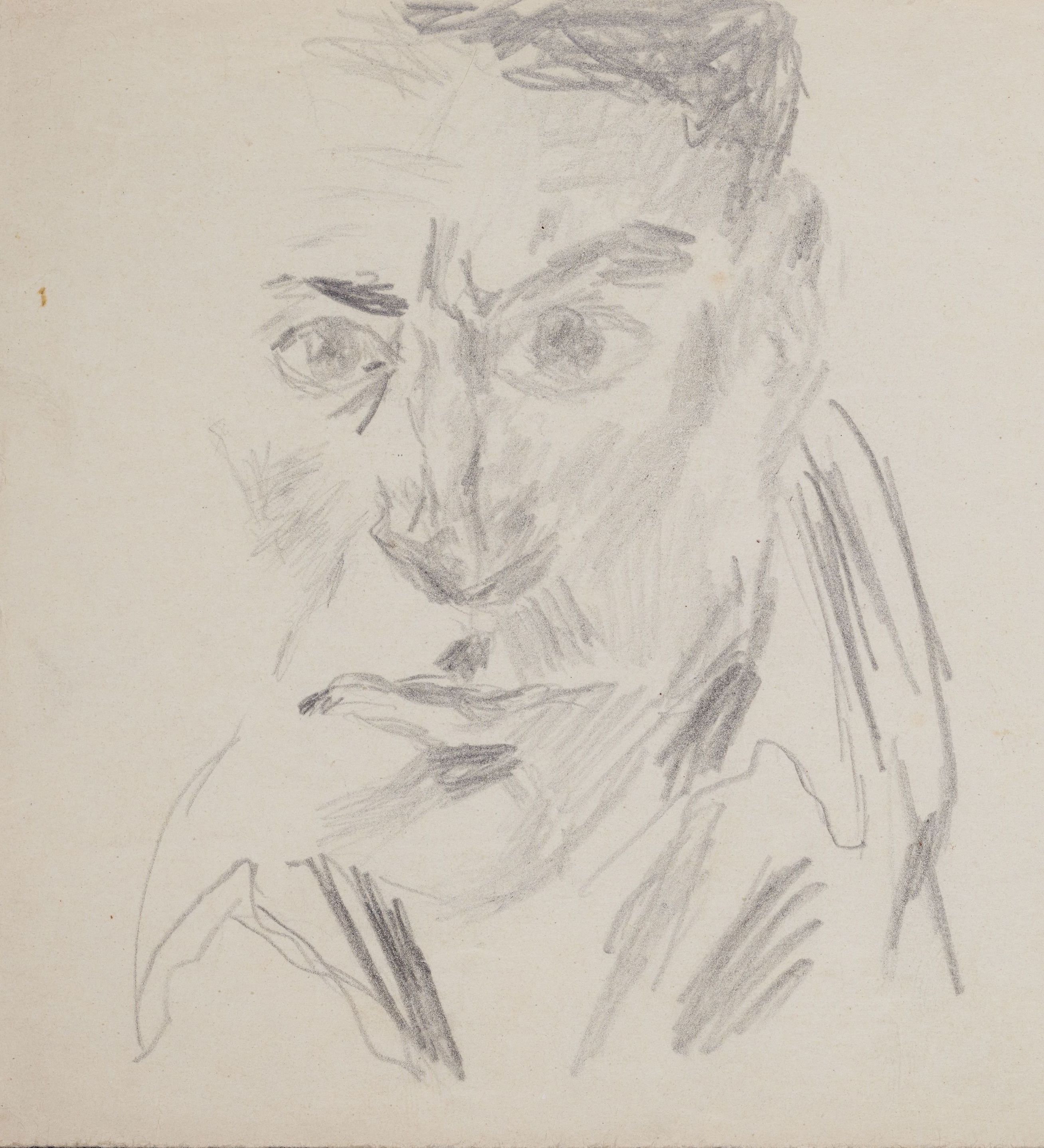

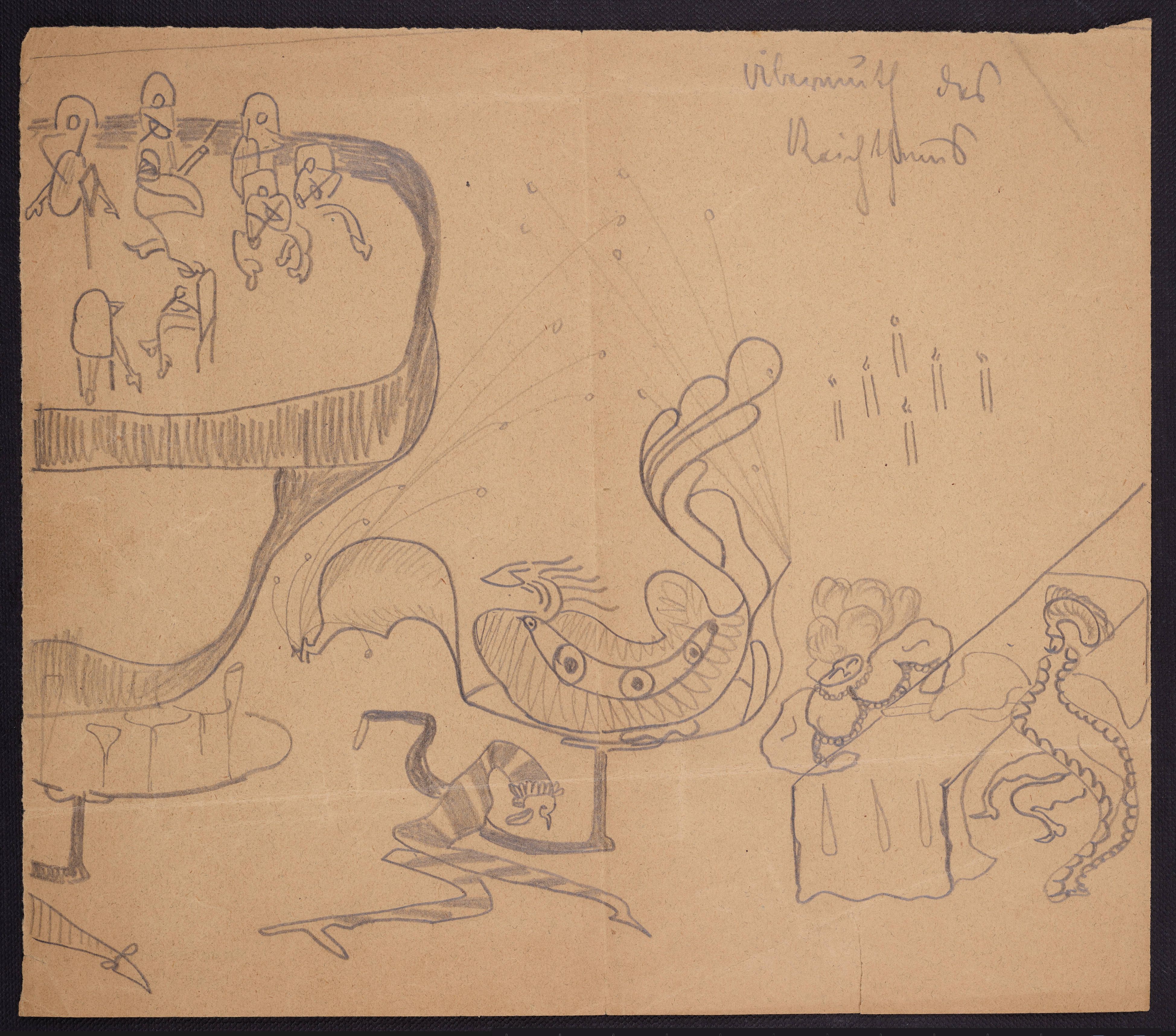

Self-portrait, 1911 (ARC. 4* 2000 05 086 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel)

Self-portrait, 1911 (ARC. 4* 2000 05 086 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel)

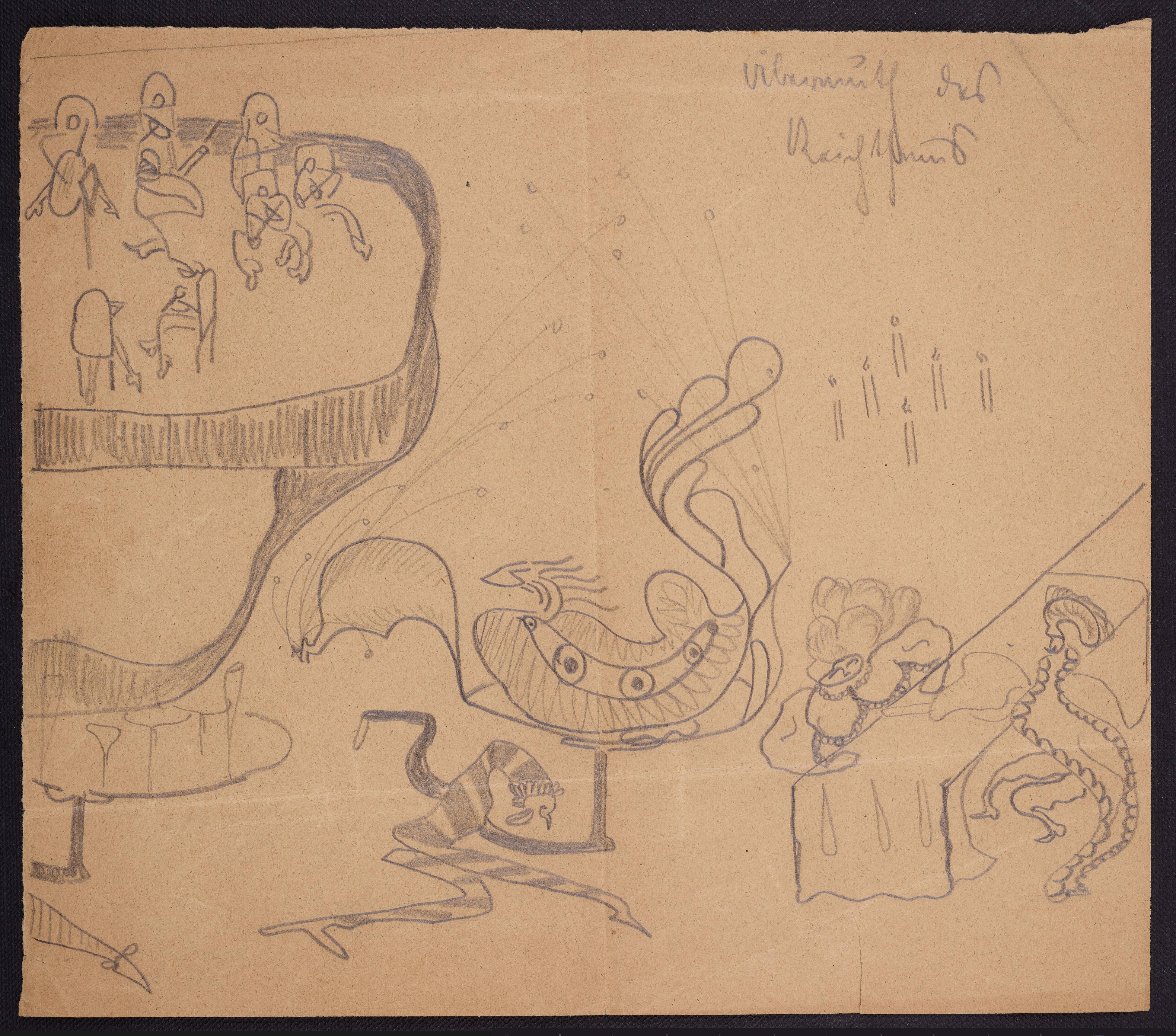

Circa 1905 pencil drawing by Kafka: "Übermuth des Reichtums,"[Wantonness of Wealth] from ARC. 4* 2000 05 074 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Circa 1905 pencil drawing by Kafka: "Übermuth des Reichtums,"[Wantonness of Wealth] from ARC. 4* 2000 05 074 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

An Old Manuscript: Restoring The Trial and Other Works

Shortly after World War I broke out, Kafka began working on The Trial in 1914, writing chapters and chapter sections in ten different notebooks. He read the first chapter aloud to Max in September 1914, who recalled that Kafka laughed so much "that there were moments when he couldn't read any further." Kafka read aloud other chapters in the following months, but abandoned the project in early 1915, leaving behind more than a dozen bundles of loose-leaf notes. He gave these to Max in 1920.

On writing The Trial, from Kafka’s diary:

August 21, 1914

"Began with such hopes and was thrown back by all three stories, today most of all. Perhaps it’s correct that work could be done on the Russian story only always after The Trial. In this ridiculous hope, which is evidently based on a mechanical fantasy, I begin the Trial again.—It wasn’t completely in vain."

September 13, 1914

"Again barely 2 pages. At first I thought the sadness about the Austrian defeats and the fear of the future (a fear that seems to me basically ridiculous and at the same time disgraceful) would hinder me altogether from writing. It wasn’t that only a dullness, which perpetually returns and must be perpetually overcome. For the sadness itself there’s time enough when not writing..."

Source: Kafka, Franz. The Diaries, Translated by Ross Benjamin, First edition, Schocken Books, 2023, pp. 355-356.

Before publishing the novel, Brod edited it, standardizing Kafka's spelling and punctuation, excising some bits, and completing other unfinished parts. Brod considered each bundle a “chapter” and arranged them in an order he thought worked. While the manuscript gave no title, according to Brod Kafka had referred to it as “The Trial” in his diaries and conversation. On April 26, 1925, Brod published The Trial. On April 26, 1925, followed by the Castle and Amerika in 1926 and 1927.

Brod offered the Jewish publishing house Schocken Verlag rights to Kafka's work and in 1935 they published The Trial, along with The Castle and Amerika, giving Kafka widespread distribution in Germany. Edwin and Willa Muir translated the first English editions (Victor Gollancz) — The Castle in 1930, The Trial in 1937, and Amerika in1938.

Brod fled to Tel Aviv in 1939, taking with him Kafka's manuscript of The Trial and other unpublished papers. Brod released a new German edition of The Trial (Schocken Books, New York, 1946) with material he had previously omitted - incomplete chapters and passages struck by Kafka. The Muirs followed with an updated English edition (Modern Library, 1956) which included new material translated by E.M. Butler. More English translations of The Trial followed, along with translations into over 50 different languages, including Czech in 1958. (Click here for more details about the publication history of Kafka's novels.)

After Max Brod's death in 1968, new German versions began to appear. The Bodleian Library, Oxford University, had received the bulk of Kafka's original manuscripts from his heirs in 1961. Malcolm Pasley, German literary scholar and editor, then began restoring the original German texts to their unexpurgated and unfinished state, including Kafka's unique punctuation, considered critical to his style. In 1982 S. Fischer Verlag published The Castle as a two-volume set — the novel in the first volume, and the fragments, deletions, and editor's notes in the second volume.

Similarly, after Kafka's original manuscript of The Trial was auctioned to the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, Germany in 1988, Pasley and his team set to work again. They published the new critical edition Der Prozess, also as a two-volume set, with S. Fischer Verlag in 1990. An historical-critical edition, Der Process, published by Stroemfeld/Roter Stern Verlag followed in 1995, complete with a facsimile of Kafka's own handwriting, rather than a printed transcription of it, displaying all Kafka's changes. This edition consists of sixteen individually bound booklets, each corresponding to a segment of the original manuscript. They are interchangeable and can be read in any conceivable order.

New German editions of The Trial (1990 and 1995)

New German editions of The Trial (1990 and 1995)

Pasley's work restoring Kafka's original manuscripts informed new English translations and in the 1990s, Schocken began publishing these, including Breon Mitchell's translation of The Trial (1998) and Mark Harman's translations of The Castle (1998) and Amerika: The Missing Person (2008).

Kafka left behind a diary (1910-1924), which Brod edited as he did the novels. A two volume English edition came out, the first volume translated by Joseph Kresh in 1948 and the second one by Martin Greenberg in 1949, with the cooperation of Hannah Arendt, who was then editorial director of Schocken Books.

S. Fischer Verlag published an uncensored German edition of the diaries in 1990. Using this restored edition and Kafka's original entries, which included self-reflections, records of daily events, and drafts of literary works, Ross Benjamin began working on a new English translation of Kafka's diaries in 2014, with the aim of catching Kafka in the act of writing and presenting the diaries not as a cohesive whole, as Brod’s version did. Schocken published Benjamin's translation of The Diaries in 2022, complete with spelling mistakes, scraps of abandoned stories, and entries that break off in mid-sentence and appear to be out of sequence.

Today the Bodleian and Marbach Libraries are not the only ones holding Kafka’s original works. When Brod died in 1968 he left his literary estate to his secretary Esther Hoffe. The Tel Aviv court ruled that Brod had explicitly ordered Hoffe to catalogue and transfer his papers to a public archive. In 2016, Israel's National Library was awarded the papers and manuscripts and began collecting them from sites in Israel, Germany, and a Swiss bank vault. They have since been digitizing the collection and making it available online.

Self-portrait, 1911 (ARC. 4* 2000 05 086 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel)

Self-portrait, 1911 (ARC. 4* 2000 05 086 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel)

Circa 1905 pencil drawing by Kafka: "Übermuth des Reichtums,"[Wantonness of Wealth] from ARC. 4* 2000 05 074 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Circa 1905 pencil drawing by Kafka: "Übermuth des Reichtums,"[Wantonness of Wealth] from ARC. 4* 2000 05 074 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Virtual Keynote:

February 26, 2026

3:00 EST

with Ross Benjamin, Stefan Litt, and Steve Stern

We'd like to thank

The National Library of Israel for partnering with us

and this year's Birss Fellows --

Ignacio Burgos, Abigail King, and Abigail Lebowitz

With special thanks to

Roger Williams University alumnus, Robert Blais '70, for endowing the John Howard Birss, Jr. Memorial Program